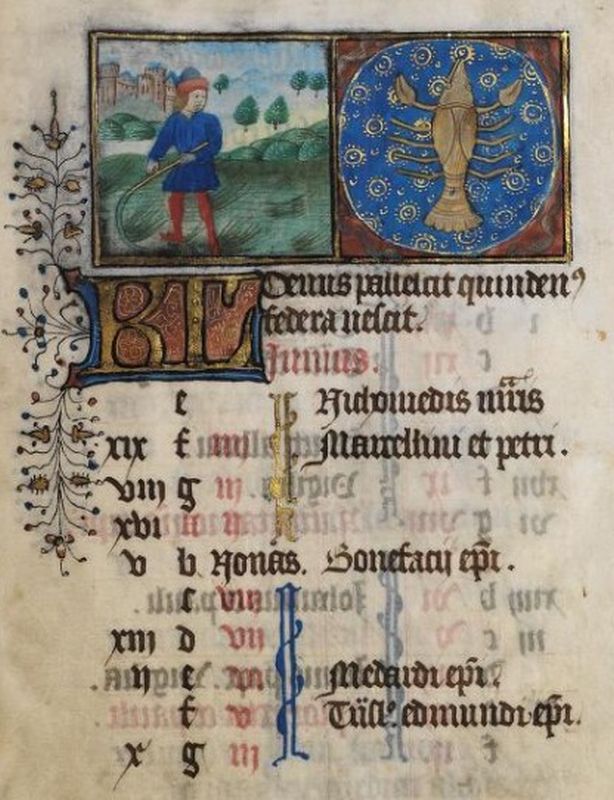

As much of medieval life was centred around religious belief, the daily services of the church (Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline) helped to mark the passing of time, particularly for those in holy orders. Consequently, one of the most common types of manuscript to be found in medieval homes were those that allowed the laity to observe these services – known as the ‘books of hours’.

For those who could afford them, books of hours were often richly illustrated, and could serve just as much of a decorative purpose as a religious one. But for the average lay person, life was more concerned with the farming year and the passing of the seasons. Many books of hours included illustrations of agricultural tasks which were carried out at various times of the year, such as sowing crops, harvest time, or tree felling, often associated with the various feast days across the year.

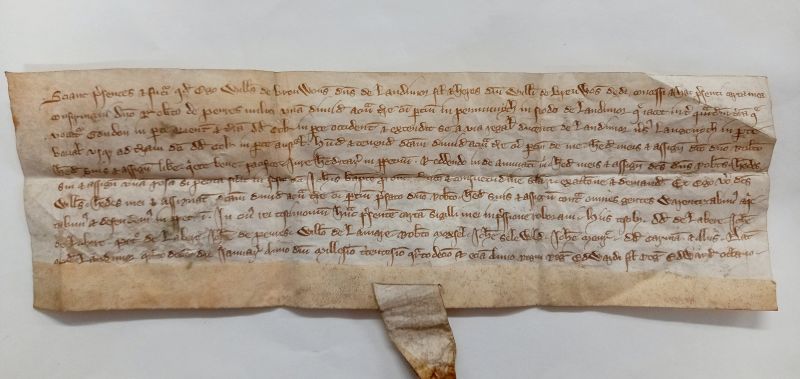

In a legal sense, these holy and saints’ days were also commonly used in medieval charters to record the date. Hundreds of examples of this practice can be seen in the collection of the charters of Margam Abbey, Glamorgan, part of the Penrice and Margam Estate Records at NLW.

Margam Abbey was founded in 1147 as a daughter-house of the Cistercian order at Clairvaux and was endowed with a large amount of land by Robert, earl of Gloucester (Penrice & Margam charter no. 1). By the late 13th century, Margam was Wales’s richest monastery, owning land and granges in both Wales and England, and Gerald of Wales wrote of Margam in his Itinerarium Cambriae (c.1191) that it was ‘by far the most renowned for alms and charity’. As a result, the Margam Abbey charters, including those of the Penrice and Mansel families, comprise one of the largest and most complete monastic collections in Britain. The majority of its records consist of sealed land grants to and from many of the ruling families of Glamorgan, ranging from the 12th to the 16th centuries. As well as being a source of local history for Glamorgan, Margam’s charters also help to place it in a wider European context – not only containing royal charters and letters patent, but also a number of 13th-century papal bulls (charters 82-84, 141, 171, 173-4, 185, 245) confirming the importance of Margam to the Cistercian order and dated at various locations in Europe, including Tivoli, Liege, Rome, and the Lateran.

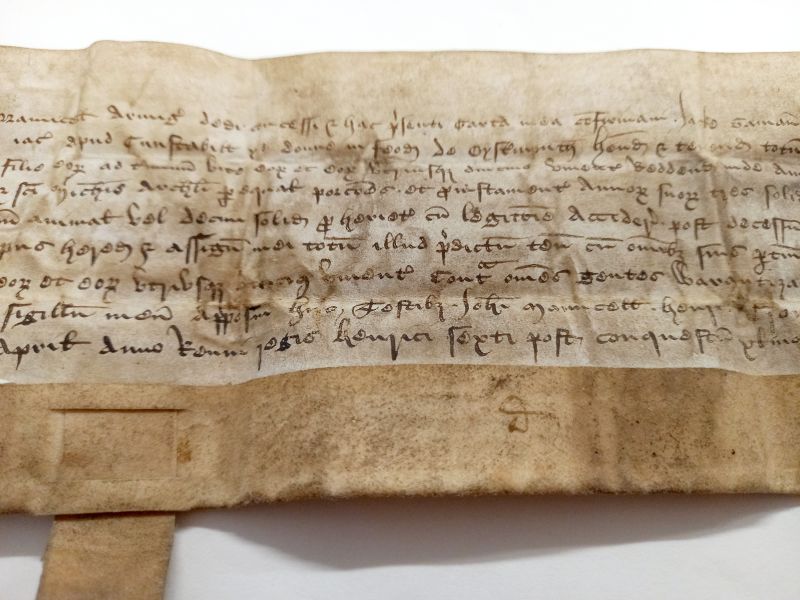

Typically, each charter records the day upon which it was signed or sealed, usually given as a feast day or saints’ day, and the year of the reigning monarch. Midsummer Day or Heuldro’r Haf - usually celebrated around the 21st June but also observed as St John’s Day or Gŵyl Ifan in medieval Wales due to the feast day of St John the Baptist falling on the 24th June - was a significant date in the farming year as it marked the longest day and the turning of seasons as the days shortened and harvest time was nearing. In Margam’s charters, Midsummer is used as a dating clause in several instances. A quit-claim by a William de Marle to Margam Abbey (charter 227, 1354) is dated Midsummer Day, while charters 193 (1312) and 228 (1357), also quit-claims to the Abbey, are dated at Margam ‘the Sunday after Midsummer’ and ‘the Saturday after Midsummer’ respectively. It is not only within land grants that this dating occurs. Charter 233 (1366), which detailed assizes recovering the Abbot of Margam’s salmon fishery from one Res [Rhys] and one Howel, stated that for their piscine thievery each were fined threepence in damages on ‘the Monday before Midsummer Day’.

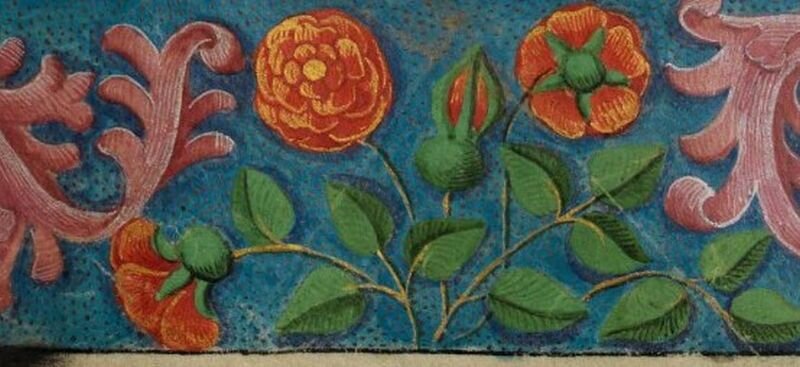

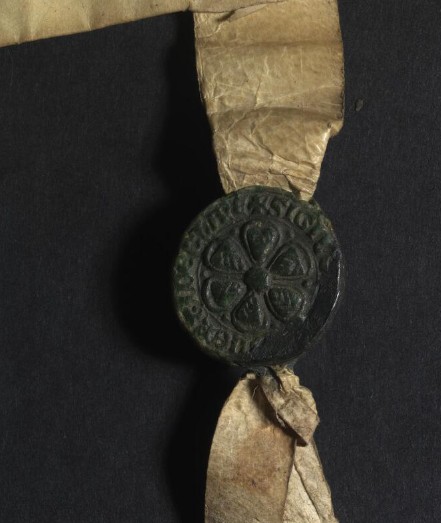

This theme of agriculture is abundant when looking at the rent requirements in some of Margam’s charters, which stipulate what is given in exchange for each piece of land. Rents could include livestock, crops, or spices, as well as money, and could stipulate a nominal amount (or ‘peppercorn’ rent) to make a legal exchange. Charter 302 (1315) asks for just ‘a rose at Midsummer’ in exchange for the rent of half an acre of land; a rose is also given in charter 329 (1383) for a burgage. Charter 306 (1315) more generously specifies a garland of roses to be given annually at Midsummer in exchange for six and three-quarter acres. Symbolically, the only time roses are stipulated to be given is at Midsummer, and they do not appear as an exchange at any other date in Margam’s charters. Roses held a certain emblematic significance in both English and Welsh heraldry in the medieval period, perhaps the most well-known example being the representation of the houses of York and Lancaster with white and red roses in the heraldry of the Tudors. Roses also featured on seals and as decoration in manuscripts.

Of course, the dates given in charters were not always reliable. Margam may have been the wealthiest Abbey in Wales but news in the medieval period travelled more slowly than today and could be hampered by events of the time. Charter 336, for example, issued during the turbulent period known as the Wars of the Roses, was dated at Oxwich, Gower, on 4th April, yet supplies the year (1461) as the reign of Henry VI, rather than that of Edward IV whose accession had been on the 4th of March. Evidently the announcement of Edward’s accession had not yet reached Gower at the time.

Margam Abbey was a prominent landmark in south Wales for nearly four centuries, but it did not survive Henry VIII’s dissolution. In 1540 Henry’s Great Seal (featuring a Tudor rose) condemned the Abbey and its lands, including its church, bell-tower, fisheries, cemetery, water-mill, and a large number of its granges to be sold to the Mansel family for £938, six shillings and eightpence (charter 359). Incidentally, the charter granting Margam’s dissolution was dated at Westminster on 22nd June. It appears that the Abbey saw its final day at Midsummer.

Category: Article