A linked data approach for bilingual name authority

Data is everywhere these days. We leave a rich trail of it wherever we go, through our phones and other smart tech, in our jobs, and every time we shop. The data we create is hugely valuable to businesses and service providers as it gives insight into our behaviour, our habits and movements. But data also has huge potential to help us learn about the past, about our ancestors and the places in which we live.

Libraries and archives have been collecting data for years; cataloguing historic papers, recording historic buildings, and describing maps and works of art. This has led to a plethora of data sources held by different institutions. For years the keepers of this knowledge have strictly adhered to their own data standards and in many cases have restricted access to protect their intellectual property.

Now, slowly but surely, things are changing. Back in 2001, Sir Tim Berners-Lee imagined the internet becoming a semantic web. A place where common data standards and ways of expressing relationships between things would create an interconnected web of knowledge across all sectors and genres. Gradually this vision is starting to be realised, at least in some quarters, thanks to linked data standards and an increasing amount of data being published openly.

One of the big success stories in semantic, or linked, data is Wikidata, a sister project of Wikipedia where the aim is to gather and connect the sum of all human knowledge as open structured data. With over 100 million data items, Wikidata already contains rich data about millions of people, past and present, places, events, artworks, wildlife, historic buildings and so on. And cultural institutions have begun aligning their data to this open dataset. So if a library has a unique identifier or an authority file for a person or a place they can add that to the relevant Wikidata item. This means you can go to a Wikidata item about a person who has an archive at The National Library of Wales and learn if they also have portraits in the National Portrait Gallery or a commemorative blue plaque. Perhaps they were born in a building that is now a listed property, or maybe they were a politician, or an Oxford alumni. This vast dataset has, quite organically, become a cultural hub, connecting knowledge from all over the world, allowing us to discover connections and relationships we simply didn't know existed.

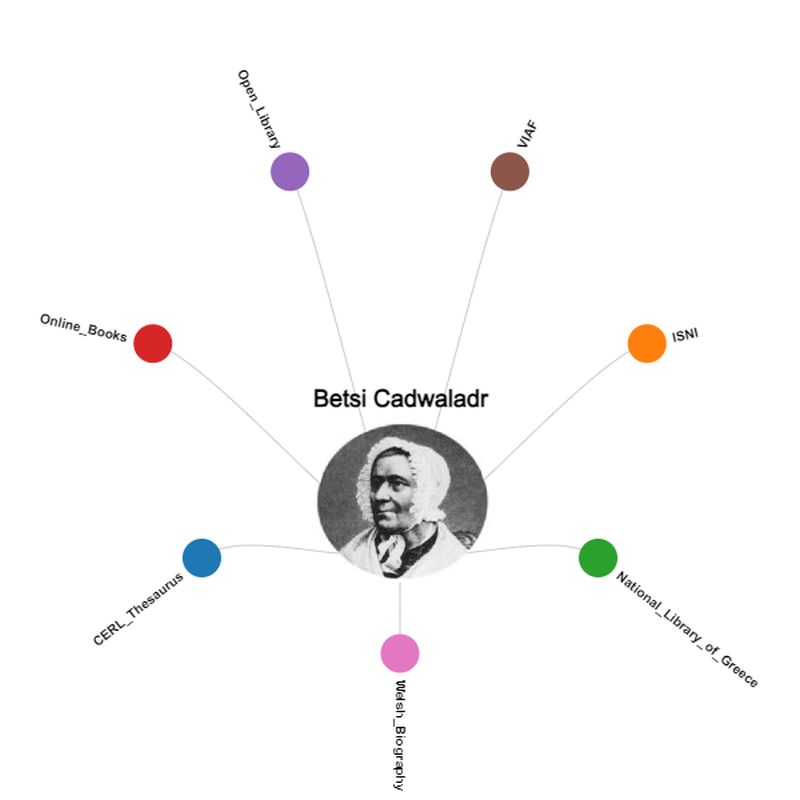

At The National Library of Wales we have been aligning metadata for our collections for a number of years, with over 50,000 wikidata items for items in our collections or about people and places in our collections. This includes an attempt to align as many of our name authority files as possible and so far over 12,000 people have been successfully aligned to Wikidata through this process.

However we’ve also been keen to help others in Wales share relevant data and so all of CADW’s listed buildings have Wikidata entries, over 10,000 items in the Coflein historic sites database have been aligned to Wikidata, including all Welsh chapels, and The Welsh Language Commissioner's entire dataset of standardised Welsh place names is now aligned. This means we can start creating links between all these datasets, which, as you might imagine, offers great opportunities for research and discovery. And Wikidata is multilingual. In recent years contributors have labelled millions of items in Welsh, meaning we can record and explore data bilingually.

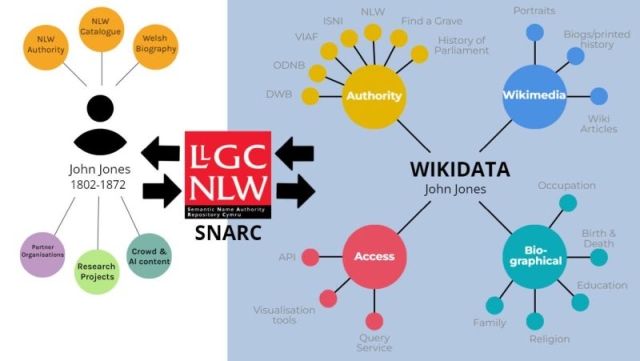

So this brings us to our latest piece of work. Wikidata is a fantastic open data resource, but its greatest qualities are also its weaknesses. The sheer size of this ever-expanding universe of data means the data model is also growing vast and complex - not the easiest thing for someone unfamiliar with the project to get their head around. Secondly - anyone can edit! This makes it a fantastic platform for crowdsourcing but, as a Library keen to roundtrip this rich data, there comes a point where we need to be able to curate, adapt and protect that data from further change, so that we can rely on it to power queries and services without fear of it changing. This is why we created the Semantic Name Authority Repository Cymru, hereafter known only as SNARC.

SNARC is a bridge between open crowdsourced data, and our own authoritative metadata. It allows us to strip back the complexities of Wikidata, customise the data structure to suit our needs and to quality control the flow of data coming in and going out.

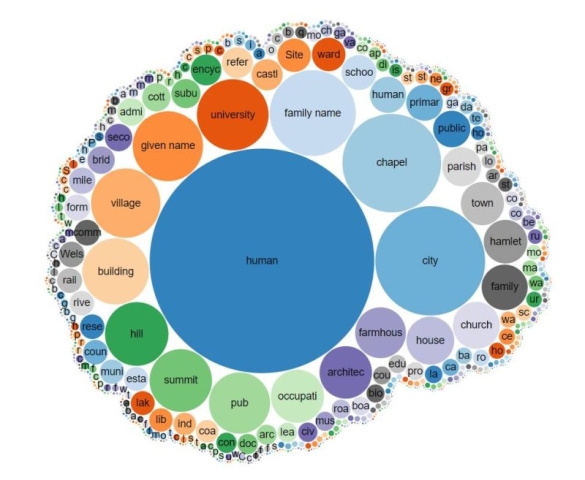

Built using Wikibase, the same software Wikidata uses, SNARC looks and feels very much like its big sister and it benefits from many of the same tools, such as the query service, upload tools and an API. It provides our users with a search interface for over 100,000 data items relating to Welsh cultural Heritage, focusing on people and place. Here is a visualisation showing all of the SNARC content by type.

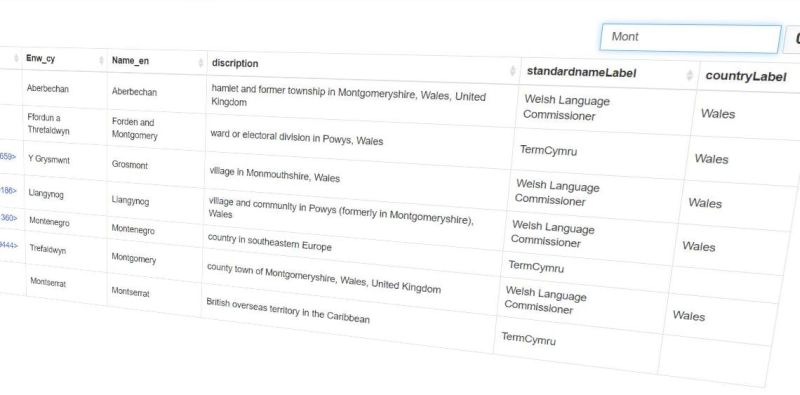

Much of the data in SNARC is imported from Wikidata, after being checked and adding any missing Welsh labels. But the dataset also includes data from our own catalogue, such as short biographies of people and links to our digital images of a given subject. For place names, we have also adopted standardised spellings, where available. Our dataset also rectifies a long-term gripe with Wikidata by allowing us to use Wales as a country. Our data is able to state that a place is in Wales, or that a person is Welsh. This isn't possible in Wikidata due to a long-standing decision that a ‘country’ must be a sovereign state.

But despite our little rebellion, we have, wherever possible, included the identifiers of the comparable entity in Wikidata on our data items. This alignment to Wikidata is not just important for reference, but it allows us to query data across both datasets at the same time. So if we want to check for updates or changes to content on Wikidata we can. We can also push improvements on SNARC back to Wikidata. But it also means that we can still access richer data from Wikidata in our queries in order to answer complex research questions.

As an example, we have data about thousands of cities in SNARC to describe where people were born, worked or died, or where a building once stood. But we have kept that data minimal. All cities are simply described as an instance of a ‘city’. Whereas in Wikidata there are many different subclasses of city. You have your megacities, big cities, port cities, global cities, million cities and so on. But because our cities are still aligned with their Wikidata items the query service magically allows you to search for all megacities on SNARC by referring back to Wikidata for the more granular data.

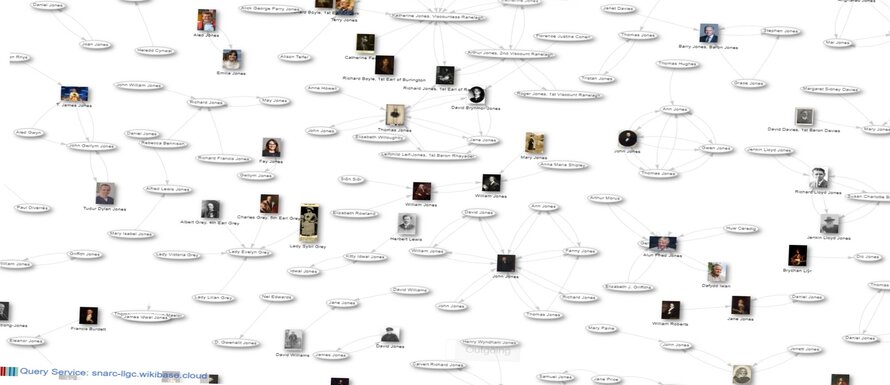

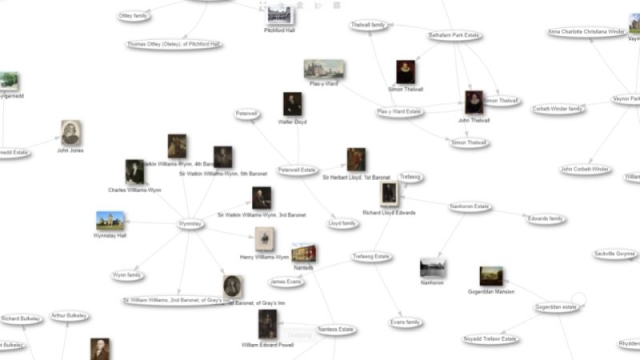

Since our database is structured data, just like Wikidata, we are able to start to realise the vision of Tim Berners-Lee. Using the query service to interrogate the data allows us to quickly identify overlap between previously separate data silos. For example we can see all historic chapels in Wales, with archives at NLW or explore the ownership of estates and country houses (CADW data) by the landed gentry (Welsh Biography and NLW data). We can even connect data about church parishes, their parish churches, and the saints to whom they are dedicated.

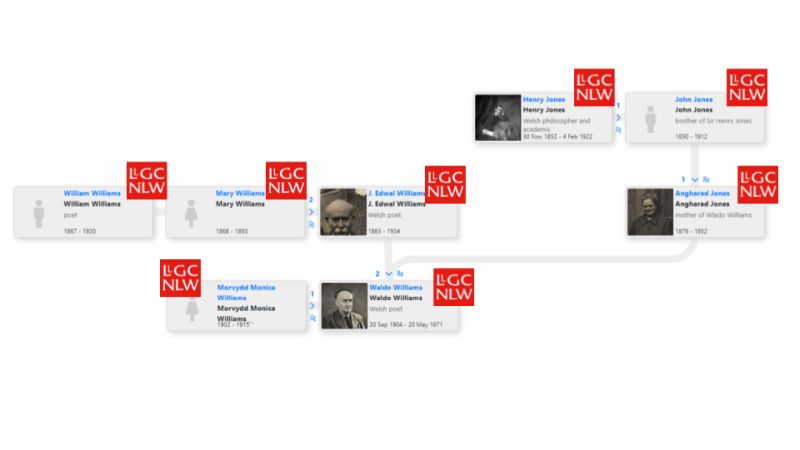

Thanks to data extracted from our own catalogue records, and data provided by other organisations and individuals via Wikidata we are also starting to build up large family groupings. We see multiple generations of families who all have archives in the library but until now were completely unconnected, for example the family tree of Waldo Williams.

Beyond the value of the information contained within this dataset, the Welsh language component is hugely valuable. All 110,000 items in the data set have a Welsh language label and description, so all the data can be visualised and reused in Welsh as well as English and we have already seen data from Wikidata used to help create Welsh language maps, apps and tools. It also means that much of our catalogue data which is traditionally only available in one language, is now available bilingually. For Wales’ listed buildings, over half now have Welsh language labels. Various lists of standardised place names, from the government's Term Cymru service and the Welsh Language Commissioner are now searchable in one place, and anyone who wants to adopt these name forms, and pull the data into their services can easily and freely do so.

So who is SNARC for? Everyone. Whether you want to look up the Welsh name of a country or a university or you want to research the 19th-century barding tradition in the South Wales valleys or perhaps explore ownership of a local mansion, this dataset can help.

And, like Wikidata we want this to be an ever-evolving project. We want to invite research projects and trusted partners to work on enriching the data further, and to use the platform to share new research output - growing the network of connections and relationships within the data.

Try it for yourself! And let us know if you have data which might add further value to this resource.

Jason Evans

Open Data Manager

Category: Article