The ‘Art of Maps’ was our theme for the 9th annual Carto-Cymru symposium at the National Library of Wales on Friday 16 May, looking at how the lines between maps and art blur, and how artistic responses can illuminate maps.

We welcomed 99 online viewers who joined around 60 attendees in Aberystwyth. Once again, we worked in partnership with our colleagues at the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW), and we were delighted to be sponsored by both the British Cartographic Society (BCS) and the Contemporary Art Society for Wales (CASW).

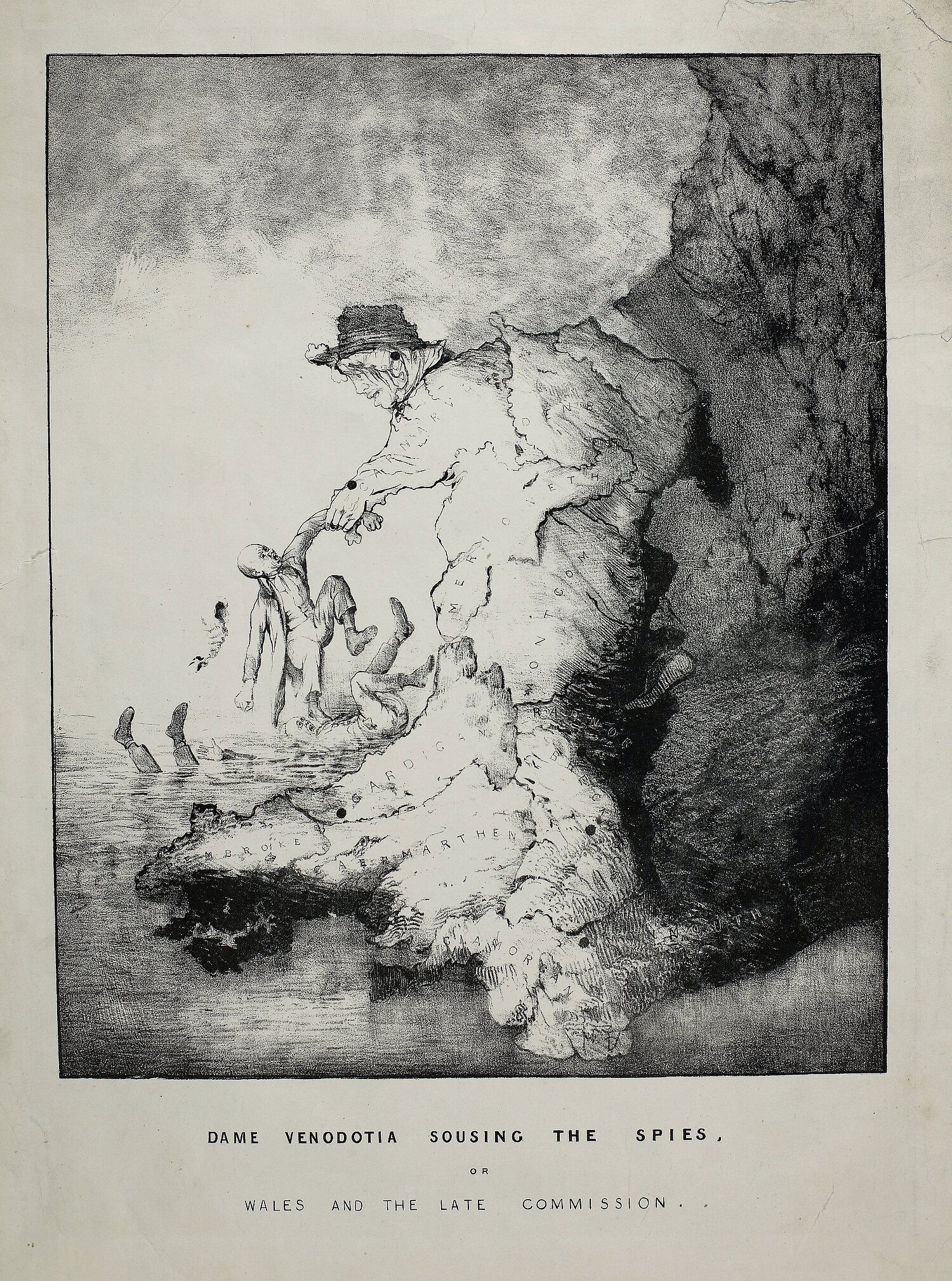

Map librarians Huw Thomas and Ellie King curated a pop-up exhibition to accompany the event, bringing out some of our most visually striking maps: the Survey of Crickhowell and Tretower, MacDonald Gill’s Wonderground Map of London Town, caricature maps by Hugh Hughes and Lilian Lancaster, Europe as the dogs of war, and an array of decorative Ordnance Survey covers.

Nodiadau-maes: field notes for the re-invention of Wales

‘Perhaps there is no return for anyone to their native land, only field-notes for its re-invention' James T. Clifford

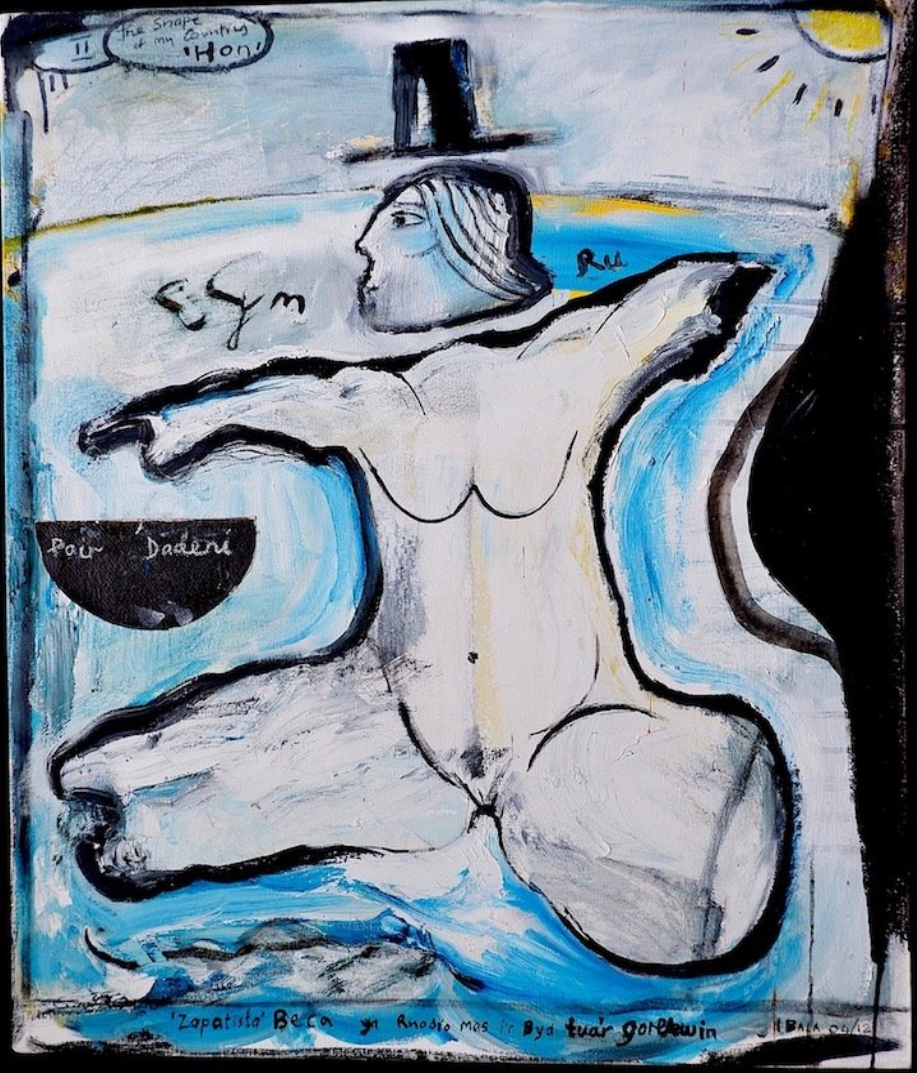

Artist Iwan Bala gave the first talk of the day with a tour through his artistic interpretation of maps. Iwan characterises his own artworks as nodiadau-maes or field notes for interpreting and reinterpreting things that are ‘simply expected’. His cartographic visualisations of Wales draw on global influences: the work of US historian James T Clifford; Welsh poet Menna Elfyn and Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar’s Logo for America. Maps of Wales thread through Iwan’s work, from the boar’s head in Mabinogi-dir, to Wales superimposed over the Celtic fringe of Europe with the Llŷn peninsula fused with Brittany, and south Wales with the Basque Country.

“Dw i'n gweld yn aml iawn ffurf Cymru, a dw i'n gweld e ym mhobman, mewn rhyw staen ar y wal... Roedd yn mynd i ryw habit i fi greu’r mapiau, siapiau ‘ma o Gymru... Cartograffiaeth o Gymru’n rhan o bob peth am Gymru, yr hanes, y beirdd, y caneuon, y chwedloniaeth, maen nhw i gyd ynghlwm yn y dirwedd”

“I very often see the form of Wales, I see it everywhere, in some stain on the wall...It became a habit for me to create these maps, these shapes of Wales... Cartography of Wales is part of everything about Wales: history, poets, songs, legends, they are all tied to the landscape.”

An abiding image is Wales in the form of a woman. Iwan linked his works on the shape of Wales to a long history of female personification of the country, and particularly to Hugh Hughes’ 1840s caricature maps of Wales as ‘Dame Venedotia’. A well-known image shows the Dame throwing the authors of the infamous ‘llyfrau gleision’ (blue books) into Cardigan Bay. These books contained a report on the state of education in Wales in the 1840s. The Blue Books were deeply unpopular in Wales because of remarks on the Welsh language, the morals of the people of Wales, and nonconformism. The Blue Books led to a belief that the only way for Welsh-speaking people to improve their lot was to learn English. This had a devastating effect on the prevalence of the Welsh language that is still being felt today. As a result, the report came to be known as 'Brad y Llyfrau Gleision', or ‘The Treachery of the Blue Books’.

Y famwlad / the motherland / corff nid llais / bodies not voices

In the spirit of reinventing and reimagining Welsh art, our second speaker was Esyllt Angharad Lewis. Esyllt is an artist and parable writer, playing with translation as an aesthetic medium.

Esyllt characterised the map work of the Beca art group (of which Iwan Bala was a prominent member) as fundamentally commenting on colonialism and colonisation of Wales by the British/English over decades and centuries, “yn llythrennol yn creithio a difwyno ei thir” / “literally scarring and defiling its land.”

Wales is made an object through the maps of the Beca group. Esyllt asks pa wrthrych? What object?

A woman.

Esyllt highlighted a tension between interpretations of the Beca group’s work: is the personification of Wales as a woman speaking about women’s suffering as well as national suffering? Or “does the way in which a woman acts as an object of desire/suffering reproduce and reinforce the idea of the motherland as old and decayed, on its knees?” ("A yw’r modd y mae menyw yn gweithredu fel gwrthrych chwant / dioddefaint yn atgynhyrchu ac atgyfnerthu’r syniad o’r famwlad hen a gwyrdröedig, ar ei chythlwng?”). Does the caricature of the female form reduce women’s suffering to a metaphor for other traumas? And why are women’s bodies so present without their voices?

Esyllt presented two works as a counterpoint: a controversial 1926 poster for the National Eisteddfod in Swansea by Evan Walters and Dyffryn Nantlle Llais Nantlle (Dyffryn Valley Voice of Dyffryn) by Mary Lloyd Jones. Mary is Wales’ most influential female landscape artist, and her work takes an abstracted view of landscapes, in particular the lead- and slate-mine-scarred valleys of mid and north Wales.

While Mary Lloyd Jones’ work maps the contours of Dyffryn Nantlle with bright colours and vibrant marks, Evan Walters’ poster for the 1926 National Eisteddfod in Swansea takes and subverts the trope of the demure ‘Welsh Lady’ (a descendant of Dame Venodotia, perhaps), depicting instead an assertive and dynamic young woman astride a dragon. Only one copy of this poster survives, thanks to the artist’s patron, suffragist Winifred Coombe Tennant. The rest were pulped for being overly sexual by the 1926 Eisteddfod authorities.

Sugarcoated history

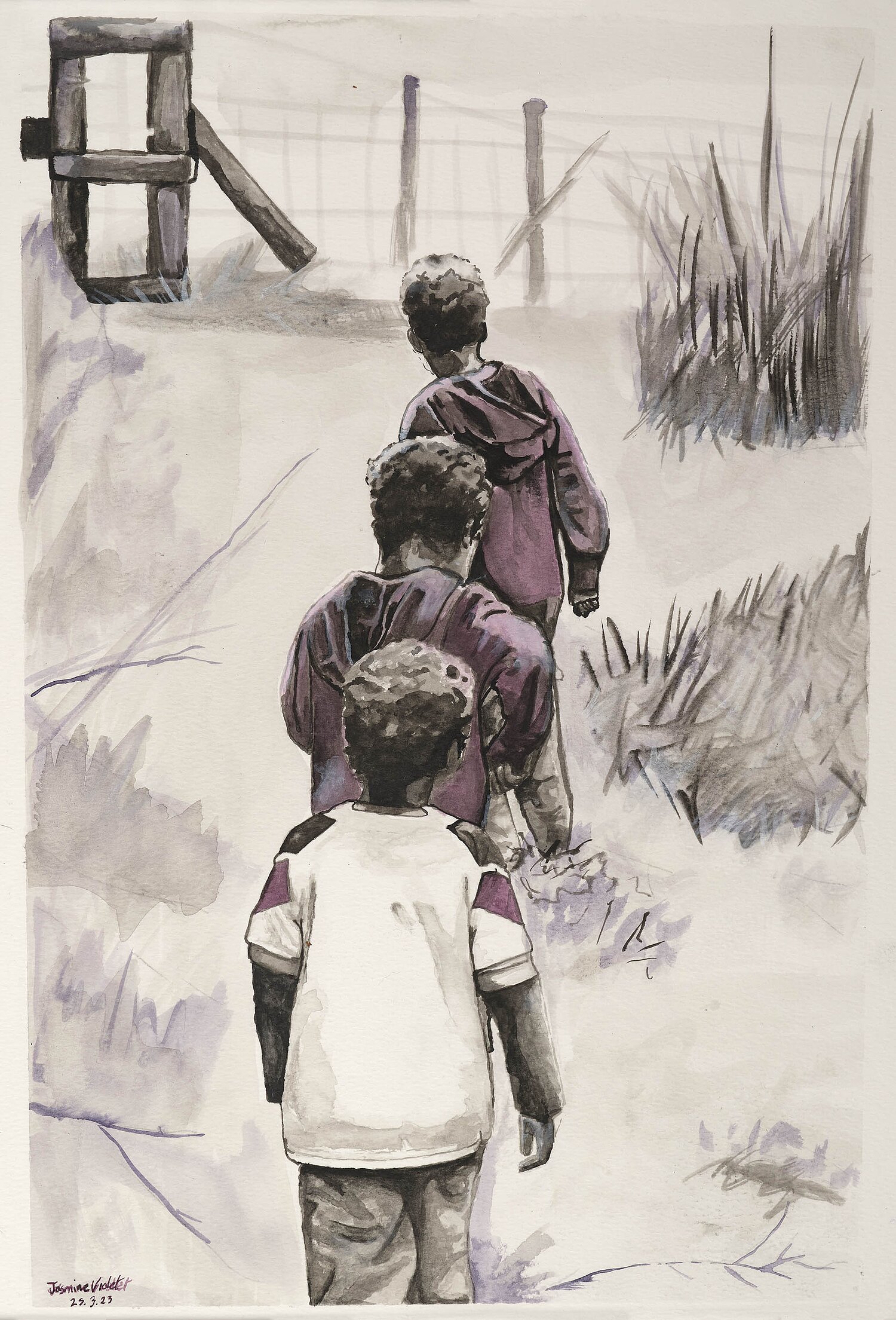

Our third speaker of the day was artist Jasmine Violet. Jasmine has worked with the National Library on our project, Dadgoloneiddio Celf / Decolonising Art. In 2023 NLW commissioned four artists of colour to create new artworks responding to our collections. Two of these projects grew from items in the map collection and had a particular focus on difficult and contested histories of slavery and colonialism.

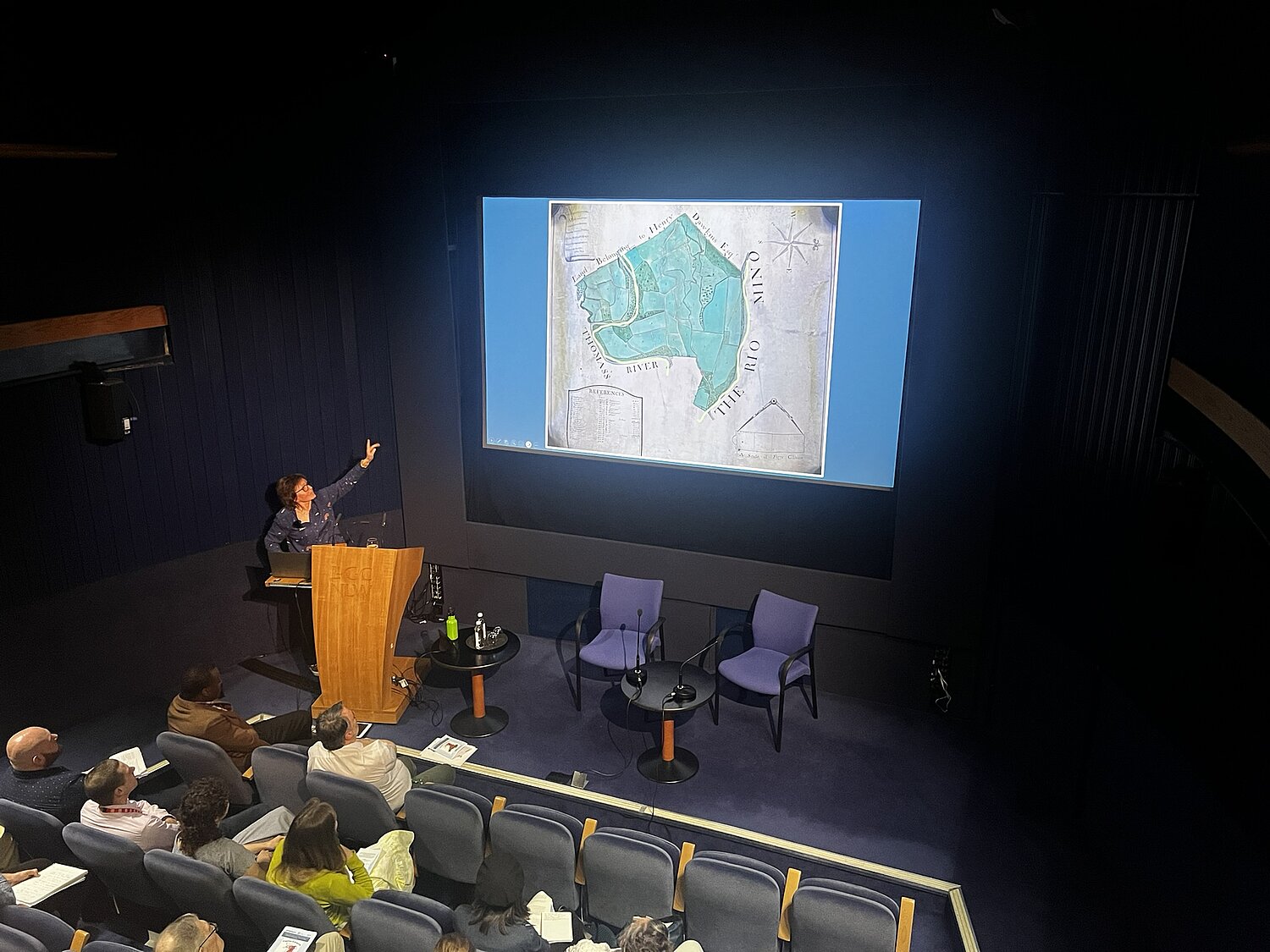

Jasmine created her work in response to connections between Wales and Jamaica in the 18th century. The National Library of Wales holds records of sugar plantations and people enslaved by Nathaniel Phillips, who would later use the wealth he gained in the Caribbean to buy the Slebech estate, five miles east of Haverfordwest. These records include a map of one of Phillips’ plantations, Pleasant Hill, and a list of the enslaved people who worked there in the 1760s.

In her talk, Jasmine made the point that global-majority artists are expected to deal with the trauma of confronting colonial items, violent items, by institutions keen to decolonise their collections. She was keen to take the project in a different direction, instead focusing her artworks on her joy in the Welsh landscape – its vibrancy, its community and the relationships she created within it.

Following on from her project with NLW, Jasmine has staged an artistic intervention as part of the Perspectives project at Penrhyn Castle in north Wales, in association with Amgueddfa Llechi Cymru / National Slate Museum and Canolfan Celfyddydau Aberystwyth Arts Centre.

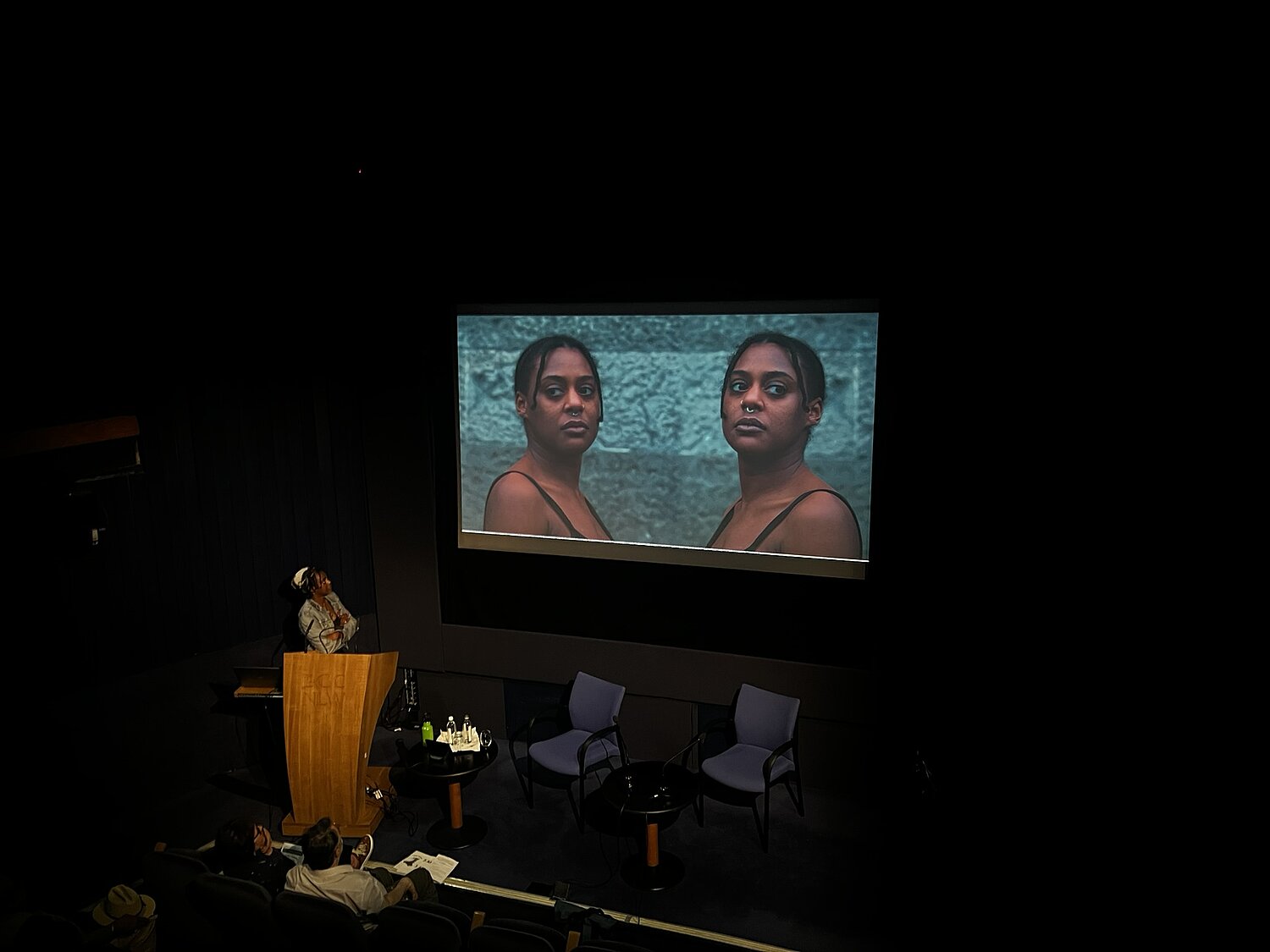

We were delighted for Carto-Cymru to be the venue for the premiere of Jasmine’s new work, the short film Sugar Coated. Jasmine deconstructs sculpture busts made of sugar, incorporating dance elements in reaction to the hidden, intertwined history of Welsh slate and the slave trade.

https://museum.wales/whatson/perspectives/perspectives-at-national-slate-museum/

Industrial landscapes of Jamaican sugar plantations

Opening the afternoon session was Marian Gwyn, honorary research associate of the Institute for the Study of Welsh Estates at the University of Bangor. She spoke on the value of manuscript plantation maps as visual records of ‘the intersections of land, exploitation, and control’.

Marian opened her talk with a plea for help: the work she presented at Carto-Cymru could not have been completed without access to Bangor Archives. The archive is at risk of existential cuts and the loss of decades of expertise. Three archival posts will be lost, leaving only one part-time post to manage both archives and printed special collections and rare books. If the collections or staff at Bangor Archives have helped your work in any way, you can send a personal message of support to communications@bangor.ac.uk

Marian encouraged the audience to think of Caribbean island colonies as oil rigs: they were never self-sufficient in either maintaining their population or providing basic commodities, and they fulfilled an entirely extractive purpose. About 70% of enslaved people in the Caribbean worked on sugar plantations, which was the largest killer of enslaved people – ahead of mining and enforced prostitution.

Maps were inseparable from the slave trade and colonisation. Herman Moll’s maps showed the routes of Spanish flotillas of treasure ships (useful knowledge for ‘merchant adventurers’), while manuscript estate maps contained extensive detail on the economics of plantations. The published maps of the time show little detail beyond the coasts, not because of lack of European settlement or knowledge, but because the land was mosaiced with plantations whose details were deemed commercially sensitive. Thus manuscript plantation maps provide one of the few sources that help us understand the landscape away from the coast. Interestingly, Marian noted that it is vanishingly rare to find Jamaican estate maps showing any form of relief. To fill this gap, she looked to plantation portraits belonging to estates in the UK. Although undoubtedly sanitised, these provide valuable insight into the landscape. In one example, the ‘great house’ used by white overseers appears on the map to be very close to the industrialised area of sugar production. However, from the portrait we can see that it was in fact on the top of a hill, overlooking the working area below, which gives a very different understanding of the power dynamics being expressed in the landscape.

Building on Jasmine’s work, Marian Gwyn drew another link between Jamaica and the Pennants of Penrhyn Castle. The Penrhyn slate quarry was a very early adopter of industrial practices, allowing it to grow much quicker than its rivals. Marian suggests that this extensive experience of creating industrialised landscapes on Jamaican sugar plantations, was successfully transplanted to north Wales. She argues that the hallmarks of industrialisation — separation of skills, concentration of labour, and the separation of owners from land — were present in Jamaica from the late 1600s, well ahead of the process in the UK.

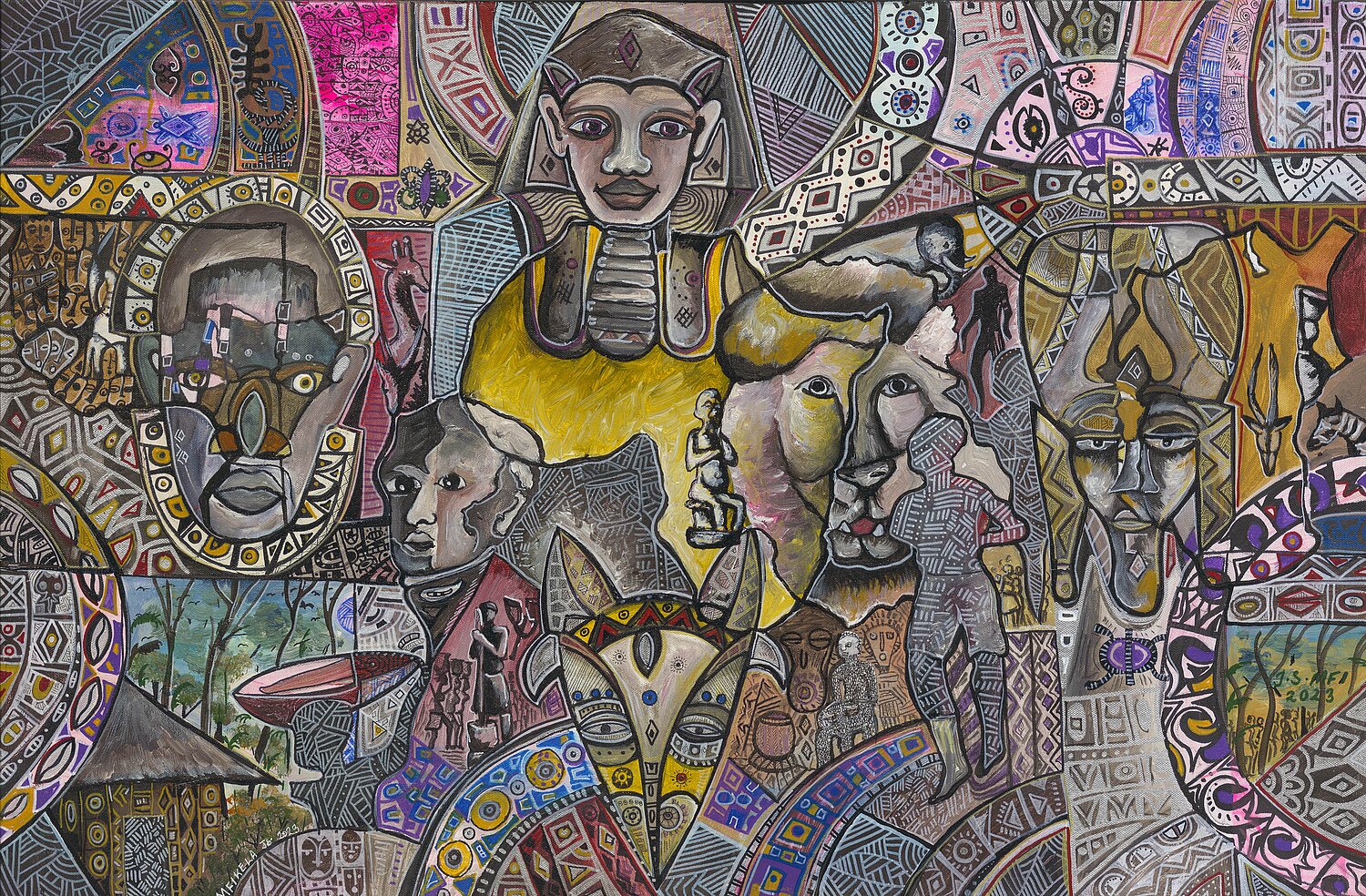

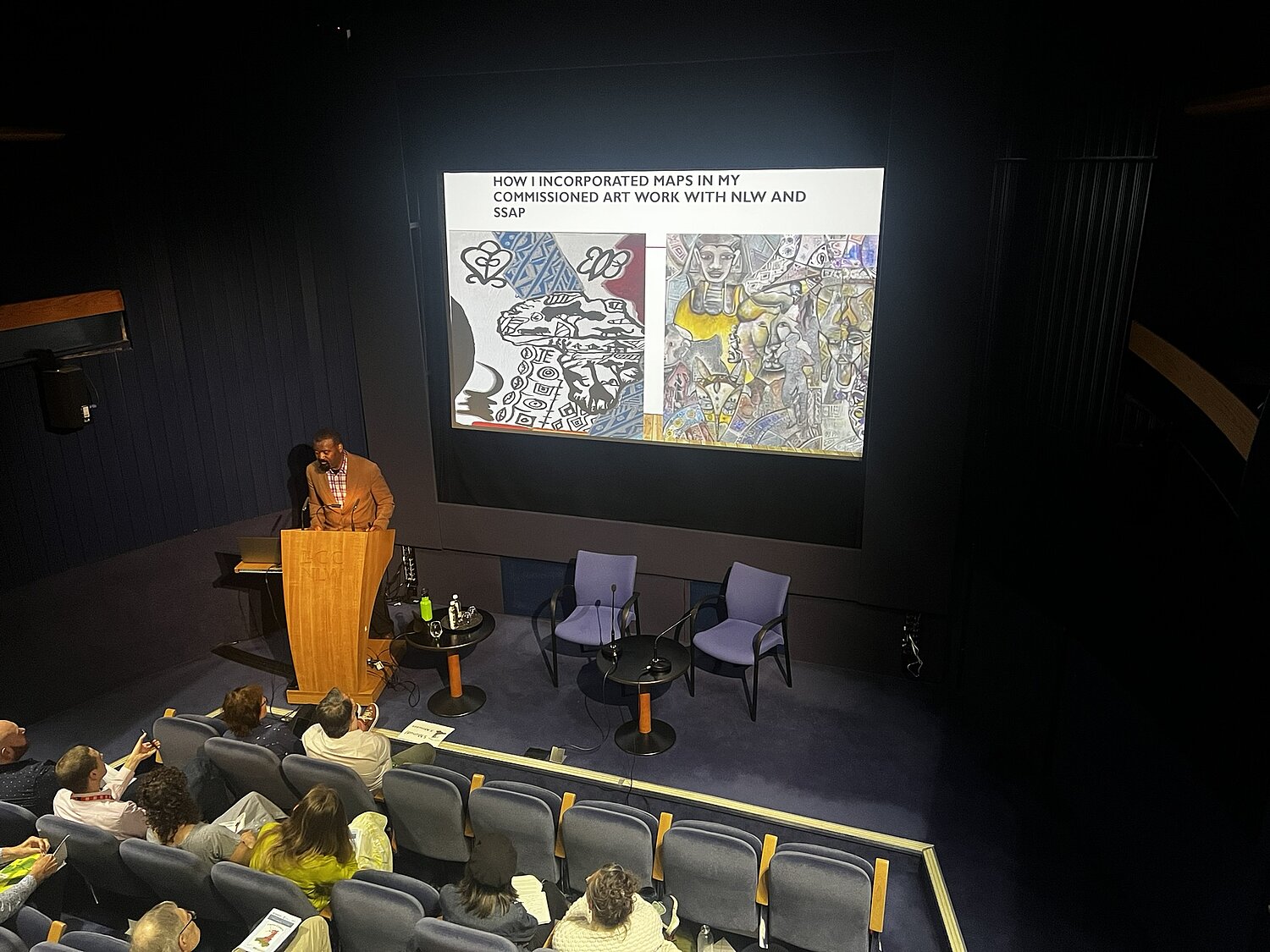

More than just directions

Rounding off the day was artist Mfikela Jean Samuel. Mfikela created another of the artworks commissioned as part of the Decolonising Art project, and he spoke about the journey he had taken through the project in understanding maps as more than a way of getting from A to B. On the maps of Africa he saw through the project, he said: “When you see a railway on a map, that is not just a line. It means movement, of people and resources. That is there because it serves the colonial masters”. On the Central Office of Information map of West Africa Mfikela used as part of the project, there is a decorative border with figures and landscape scenes. The only figure with a name, the only figure with even a face, is the explorer Mungo Park. Africans appear only as decoration, as a faceless mass, each identical to the last. Mungo Park’s face also appears in Mfikela’s work Opening the dialogue, but fractured and changed. Mfikela characterised the essence of art as representing the world not just the way it is, but the way you want it to be. This is an argument that could equally be applied to maps, marking lines to order and possess the landscape.

Recognising the artistry in maps gives us the key to a rich visual landscape, and Mfikela ended his talk with an impassioned argument for creativity as a means to create change, to imagine new worlds:

“Human progress is not inevitable; it requires the action of individuals... If you leave here today as the same person, that is a choice. This is an invitation to become an artist.”

Iwan Bala’s For Wales See England and Mfikela Jean Samuel’s Thomas Pennant are on display in the exhibition Dim Celf Cymreig? / No Welsh Art? at NLW until 6 September. NLW has a significant collection of works by the Beca art group, many of which are new acquisitions.

Works produced by Jasmine Violet and Mfikela Jean Samuel for the Decolonising Art project are on short-term display in NLW’s Peniarth Room. The commissions were funded by Welsh Government as part of the Anti-racist Wales Action Plan.

A sneak preview of Jasmine Violet’s Sugar Coated is available on her Instagram here: https://www.instagram.com/reel/DJjMRlEuAKh/

National Library digitised artworks:

Gorchydd gwraig / Woman drapery / Celtic Woman / Wales map 1986 by Paul Davies

Dyffryn Nantlle Llais Nantlle by Mary Lloyd Jones